One of the high points of Ryan Murphy’s highly anticipated FEUD: Capote vs The Swans was the casting of Demi Moore as socialite and suspected murderess Ann Woodward. In the pilot, while Truman gossips with his gaggle of rich bitch besties at La Côte Basque, the lunch is crashed by Woodward, the black sheep (and swan) of their social scene. In the midst of her homophobic slur and Gewurztraminer toss, I could only marvel at how good Moore, a recent sexagenerian, looked. I rewound the scene several times, imagining the punishing diet and draconian procedures she’d undergone to keep her face and body so youthful at 61.

One of the high points of Ryan Murphy’s highly anticipated FEUD: Capote vs The Swans was the casting of Demi Moore as socialite and suspected murderess Ann Woodward. In the pilot, while Truman gossips with his gaggle of rich bitch besties at La Côte Basque, the lunch is crashed by Woodward, the black sheep (and swan) of their social scene. In the midst of her homophobic slur and Gewurztraminer toss, I could only marvel at how good Moore, a recent sexagenerian, looked. I rewound the scene several times, imagining the punishing diet and draconian procedures she’d undergone to keep her face and body so youthful at 61.

For late boomers and Gen Xers, Demi Moore is a household name. With turns in the most iconic films of the 80s and 90s, she built a stellar career. After her debut as a self-destructive shopaholic in St. Elmo’s Fire, and breakout as a distressed widow in Ghost, Moore’s roles honed in on her physique and husky voice. She had a boob job to play the first mainstream pole dancer in Striptease, and slinked around pool tables as a faithful wife incentivized into adultery in Indecent Proposal.

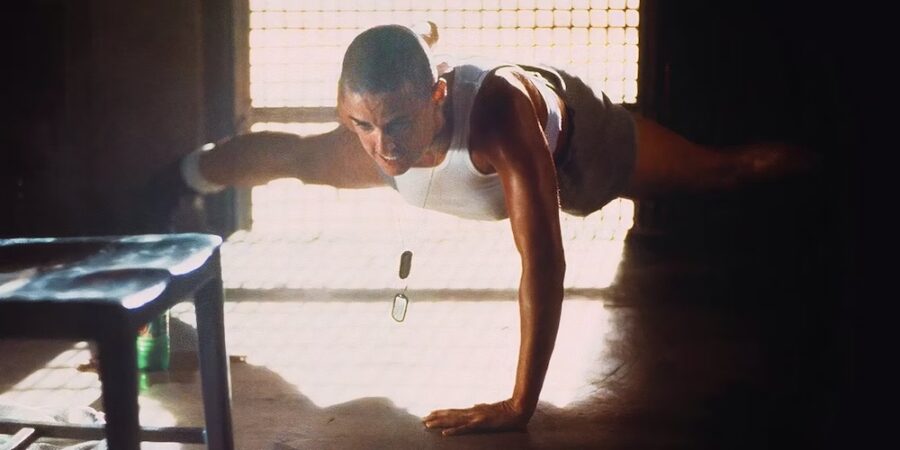

For GI Jane, she shaved her head, trained with the Navy Seals, and submitted herself to onscreen waterboarding for the privilege of yelling what women have all dreamed of saying to misogynist bullies: ”Suck my dick” with full-throated huskiness.

For GI Jane, she shaved her head, trained with the Navy Seals, and submitted herself to onscreen waterboarding for the privilege of yelling what women have all dreamed of saying to misogynist bullies: ”Suck my dick” with full-throated huskiness.

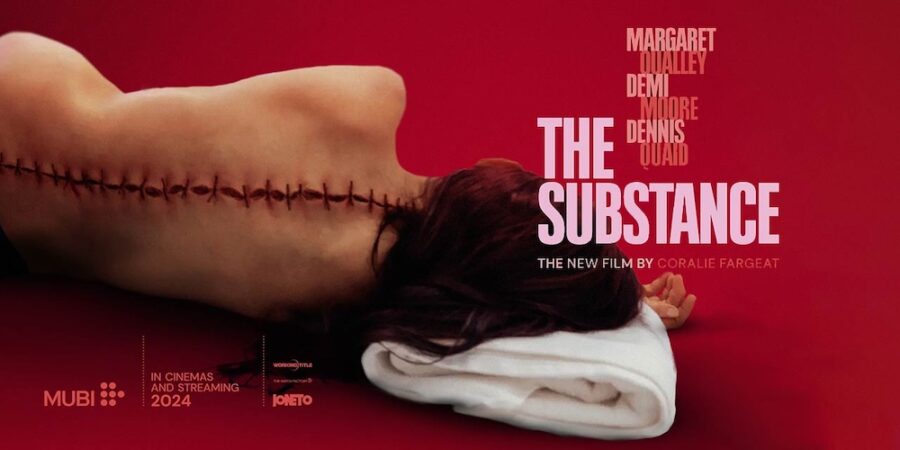

After a few decades of living under the radar, taking plum roles here and there (Charlie’s Angel, Margin Call), Moore has resuscitated her career with the meta role of her life in The Substance. As a bland, yet successful, tv aerobics instructor, the leotard-and-legging-clad Elizabeth Sparkle sparkles despite a cardio workout that wouldn’t pass muster with her previous roles or even at Lucille Roberts. In a plot mechanism by fiat, Sparkle’s age – 10 years younger than Moore’s in real life – despite her lean, lithe figure, is suddenly a deal-breaker. She resorts to drastic measures to reverse it in a Faustian bargain with more than a whiff of The Picture of Dorian Gray.

After a few decades of living under the radar, taking plum roles here and there (Charlie’s Angel, Margin Call), Moore has resuscitated her career with the meta role of her life in The Substance. As a bland, yet successful, tv aerobics instructor, the leotard-and-legging-clad Elizabeth Sparkle sparkles despite a cardio workout that wouldn’t pass muster with her previous roles or even at Lucille Roberts. In a plot mechanism by fiat, Sparkle’s age – 10 years younger than Moore’s in real life – despite her lean, lithe figure, is suddenly a deal-breaker. She resorts to drastic measures to reverse it in a Faustian bargain with more than a whiff of The Picture of Dorian Gray.

When films are pitched to studios, it’s very common to start with a simple elevator pitch of comparisons. In this case, I suspect the shorthand for The Substance was Snow White meets The Fly: an aging woman, enabled by technological means to maximize her worst impulses, is driven to steal and ingest youth and beauty. A sexier element of the pitch was undoubtedly The Substance as overdue feminist body horror, care of Naomi Wolf’s The Beauty Myth, a description embraced and lauded by most critics.

When films are pitched to studios, it’s very common to start with a simple elevator pitch of comparisons. In this case, I suspect the shorthand for The Substance was Snow White meets The Fly: an aging woman, enabled by technological means to maximize her worst impulses, is driven to steal and ingest youth and beauty. A sexier element of the pitch was undoubtedly The Substance as overdue feminist body horror, care of Naomi Wolf’s The Beauty Myth, a description embraced and lauded by most critics.

Far from a radical feminist avatar, the heroine Sparkle, like her younger doppel Sue, is someone for whom the beauty economy works. Blessed with long, black hair, a figure that’s feminine without being overtly sexual, features that read as neither plain Jane nor aggressively exotic, she lives in a glass tower decorated and demarcated by her image, one that’s repeatedly projected on television and plastered on billboards. In her living room, Sparkle reclines in front of a massive, deifying tableau of herself at her peak, as the platonic ideal of fitness and beauty.

Far from a radical feminist avatar, the heroine Sparkle, like her younger doppel Sue, is someone for whom the beauty economy works. Blessed with long, black hair, a figure that’s feminine without being overtly sexual, features that read as neither plain Jane nor aggressively exotic, she lives in a glass tower decorated and demarcated by her image, one that’s repeatedly projected on television and plastered on billboards. In her living room, Sparkle reclines in front of a massive, deifying tableau of herself at her peak, as the platonic ideal of fitness and beauty.

Despite the stunning composition and artistic direction, for a satire of beauty standards, the aesthetics represented on screen in The Substance are hardly contemporaneous with current ideals. Fargeat’s efforts to adapt Naomi’s Wolf’s excruciatingly persnickety jeremiad against the intersection of fashion, beauty, and sex into a cinematic language are anachronistic by necessity. To make its point, The Substance paints the realpolitik and fantasy of beauty as a little shop of horrors of yore in which torture is the norm.

Despite the stunning composition and artistic direction, for a satire of beauty standards, the aesthetics represented on screen in The Substance are hardly contemporaneous with current ideals. Fargeat’s efforts to adapt Naomi’s Wolf’s excruciatingly persnickety jeremiad against the intersection of fashion, beauty, and sex into a cinematic language are anachronistic by necessity. To make its point, The Substance paints the realpolitik and fantasy of beauty as a little shop of horrors of yore in which torture is the norm.

Unlike Sparkle’s 80s Jazzercise routine, social media shows women are taking up more intense forms of fitness from heavy lifting to primal movement, and training like athletes – like GI Jane. In a post-Kardashian era, from LA to Paris, the glut of makeup tutorials document norms in which “blackfishing” – when fairer-skinned models adopt darker makeup shades and hair styles to appear racially ambiguous – has democratized beauty standards. The darker, warmer skin tones, almond-shaped eyes, and high cheek bones to which all influencers aspire are more inclusive for most Black, Asian, Latina, and Middle Eastern women than Moore and Qualley’s Anglo-complaint features.

Unlike Sparkle’s 80s Jazzercise routine, social media shows women are taking up more intense forms of fitness from heavy lifting to primal movement, and training like athletes – like GI Jane. In a post-Kardashian era, from LA to Paris, the glut of makeup tutorials document norms in which “blackfishing” – when fairer-skinned models adopt darker makeup shades and hair styles to appear racially ambiguous – has democratized beauty standards. The darker, warmer skin tones, almond-shaped eyes, and high cheek bones to which all influencers aspire are more inclusive for most Black, Asian, Latina, and Middle Eastern women than Moore and Qualley’s Anglo-complaint features.

As for the idealized female body, however pert Sue’s glutes are, most women in the gym are chasing a much rounder silhouette. Far from the asphyxiating corsets, tapeworm pills, Weight Watchers weigh-ins of pre-ERA eras, the rules and standards of beauty are being re-written by women in a sterling example of female agency.

As for the idealized female body, however pert Sue’s glutes are, most women in the gym are chasing a much rounder silhouette. Far from the asphyxiating corsets, tapeworm pills, Weight Watchers weigh-ins of pre-ERA eras, the rules and standards of beauty are being re-written by women in a sterling example of female agency.

The most passionate lovers of The Substance also hail it as a feminist sendup of the male gaze, a grad school term bastardized by the need for endless discourse. In an effort to gender politic the basic mechanics of the cinematic experience, this cornerstone of feminist film theory asks us to interrogate our viewing of the female form without offering a realistic corrective other than Ludovico’s Technique or closing our eyes.

The most passionate lovers of The Substance also hail it as a feminist sendup of the male gaze, a grad school term bastardized by the need for endless discourse. In an effort to gender politic the basic mechanics of the cinematic experience, this cornerstone of feminist film theory asks us to interrogate our viewing of the female form without offering a realistic corrective other than Ludovico’s Technique or closing our eyes.

Despite the film’s efforts to demonize the judgemental lechery of male characters as the culprit for the all the rot in the female psyche, the most expressionist moments and horror-adjacent tropes fashioned by Forgeat’s direction are based in female looking. A majority of the shots in The Substance linger in medium and close-ups of Sparkle and Sue. Like Narcissus, they stare at themselves endlessly on billboards, television screens, and home decor, at their mirrored reflections and each other in various states of consciousness, plunged in that heady mix of pride and self-loathing.

Despite the film’s efforts to demonize the judgemental lechery of male characters as the culprit for the all the rot in the female psyche, the most expressionist moments and horror-adjacent tropes fashioned by Forgeat’s direction are based in female looking. A majority of the shots in The Substance linger in medium and close-ups of Sparkle and Sue. Like Narcissus, they stare at themselves endlessly on billboards, television screens, and home decor, at their mirrored reflections and each other in various states of consciousness, plunged in that heady mix of pride and self-loathing.

The emotional climax of the film kicks off with the proverbial shot of a woman looking at herself, while at her vanity, gussying up for a date. After donning a figure-hugging red dress, Sparkle jeujes her hair and applies a matching lipstick. Satisfied with the woman staring back at her, the master version of herself, not the copycat celebrity, is ready for male adoration, until a larger, more deified tableau of the doppel stares back at her mockingly in true nemesis fashion.

Is the male gaze to blame for this? Or some other foment of vanity and Icarian ambition in a fame and economic hierarchy rendered just as cutthroat by mother nature as by privilege? When Sparkle returns to the mirror and descends into a vortex of doubt and self-loathing, it’s nurtured and catalyzed by the female gaze. For all its didacticism about the male gaze, The Substance feeds off an equally toxic and lethal female gaze.

Is the male gaze to blame for this? Or some other foment of vanity and Icarian ambition in a fame and economic hierarchy rendered just as cutthroat by mother nature as by privilege? When Sparkle returns to the mirror and descends into a vortex of doubt and self-loathing, it’s nurtured and catalyzed by the female gaze. For all its didacticism about the male gaze, The Substance feeds off an equally toxic and lethal female gaze.

From the first set piece, The Substance announces itself as an exercise in homage and postmodernism, boasting its horror bonafides with a constant stream of wink-wink pastiche to iconic scare moments, from the early tracking shot of Kubrick’s geometric carpeting, then down a Cronebergian rabbit hole of bodily mutilation, and to the gory, unforgettable climax à la Stephen King. Like the vapid, cellulite-free Sue, the film descends into an orgy of overwrought references, abandoning its promise of modern expressionism and Elizabeth Sparkle’s original conundrum for B movie pandering.

From the first set piece, The Substance announces itself as an exercise in homage and postmodernism, boasting its horror bonafides with a constant stream of wink-wink pastiche to iconic scare moments, from the early tracking shot of Kubrick’s geometric carpeting, then down a Cronebergian rabbit hole of bodily mutilation, and to the gory, unforgettable climax à la Stephen King. Like the vapid, cellulite-free Sue, the film descends into an orgy of overwrought references, abandoning its promise of modern expressionism and Elizabeth Sparkle’s original conundrum for B movie pandering.

It’s not controversial to point out that the most engaging films take after their protagonists. J. Robert Oppenheimer, like Nolan’s biopic, is portrayed as layered, conflicted underneath and slick on the surface – a tension held together by pyrotechnics. Gerwig’s Barbie similarly apes its namesake in a brief existential crisis that reverts to an innately saccharine identity. The Substance, however, takes its cues from Sue, the vapid, vain, and preening villain who invites us to stare, gaze and even gawk at her gratuitous exhibitionism.

In my excitement for The Substance and a new wave of prestige cinema concerned with eternally feminine subjects such as beauty and fashion, I’d anticipated a worthy followup to Coralie Fargeat’s debut Revenge. As much an underdog as its heroine, the blood-soaked thriller excels in unexpected violence and pays off the revenge porn premise with a climax on par with Greek tragedy. Like Alabama Worley gone nuclear, and unlike The Substance, the protagonist in Revenge has no time for vanity, pastiche, or feminist film theory. She’s too busy fighting like hell to survive, reclaim her agency, and bootstrap her way out of victimhood into triumph.

In my excitement for The Substance and a new wave of prestige cinema concerned with eternally feminine subjects such as beauty and fashion, I’d anticipated a worthy followup to Coralie Fargeat’s debut Revenge. As much an underdog as its heroine, the blood-soaked thriller excels in unexpected violence and pays off the revenge porn premise with a climax on par with Greek tragedy. Like Alabama Worley gone nuclear, and unlike The Substance, the protagonist in Revenge has no time for vanity, pastiche, or feminist film theory. She’s too busy fighting like hell to survive, reclaim her agency, and bootstrap her way out of victimhood into triumph.